Siam Death Railway

இந்தப் பக்கத்தை தமிழில் வாசிக்க: சயாம் மரண ரயில்பாதை

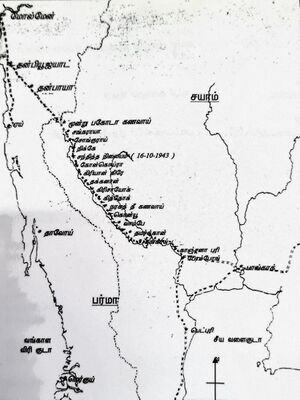

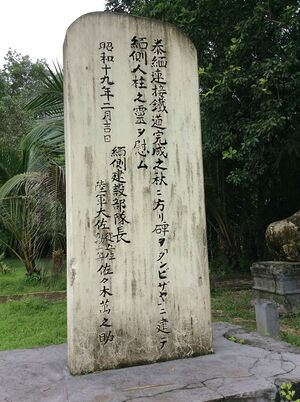

Siam Death Railway: (1942-1943) The Thailand - Burma Railway, is commonly known as the Siam Death Railway. This is a 415 km (258 miles) railway line built during World War II (September 16, 1942 - October 17, 1943). The project was undertaken by the Japanese with the aim of connecting Thailand and Burma. Approximately 180,000 to 250,000 Asian labourers and more than 60,000 prisoners of war were forcibly involved in the construction of the railway line. About 90,000 Asian labourers and more than 12,000 prisoners of war have died as a result of harsh working conditions, inadequate food supply, disease, wildlife attacks and the harsh punishment meted out by the Japanese. The Japanese government called this line the Tai - Men Rensetsu Tetsudō (Thailand-Burma Link Railway). The Thailand section of the railway continues to operate. Three trains run daily on this railway from Bangkok to Nam Tok. The bridge built during that time continues to operate too. The Burmese section of the railway which goes from the Thai border to Moulmein in Burma was abandoned many years ago.

History

The construction of a railway line between Burma and Thailand was surveyed by the British government in 1885. The project was deemed to be extremely difficult as the 282-metre-high Three Pagodas Pass on the Thai-Myanmar border and the Kwai River in western Thailand came on its way and thus the project was halted.

At the beginning of World War II, Thailand declared itself a neutral country. On December 8, 1941, Japan invaded Thailand. In 1942, the Japanese troops entered Burma via Thailand and occupied the British-occupied Burma. The Japanese had to come through the Straits of Malacca and the Andaman Sea to maintain their army forces. Also, the chances of an attack by submarines were high. A railway line from Bangkok to Rangoon was set up to avoid the perilous 3200 km sea voyage around the Malay Peninsula. This railway line is referred to by three names. They are The Burma Railway, The Death Railway, and The Burma-Siam Railway.

The railway line was planned to run from Ban Pong in Thailand to Thanbyuzayat in Burma. 111 km of railway line was laid in Burma and 304 km in Thailand. Prisoners of war from Singapore Changi Prison and other prison camps in Southeast Asia were taken north in 1942. They arrived in Non Pladuk on June 23, 1942 and built a camp for transit. Construction of the railway began on September 16, 1942, after the initial infrastructural work.

A construction team from Burma and another team from Thailand were constantly involved in the work. The logistics for the railway were imported from Malaya and Indonesia. The existing railway lines in Malacca, Singapore, Gotabhaya and Kola Lipis were renamed and used for the Siam-Burma route. The Japanese government planned to complete the project in December 1943. But the project was completed on October 17, 1943, ahead of the timeline.

The labourers from Thailand section and labourers from Burmese section, who were working on the railway line, met at Konkoita, a place which is 18kms from the Three Pagodas Pass. At present, this place is known as Kaeng Khoi Tha (Sangkhla Buri District, Kanchanaburi Province). There, the Japanese held a large prisoner of war camp during the war. Holiday was declared on October 25, 1943 to mark the completion of the railway line.

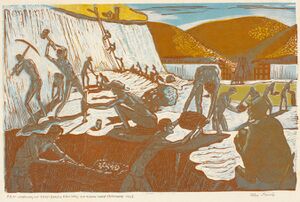

Commenting on the Siam Death Railway, American engineer Bashar Altabba said: "In history, engineers have done bigger, longer, and even harder engineering tasks in one go. But the Siam railway surpasses them because of its overall integration of different elements. These include the total length in miles, the number of bridges (six hundred bridges in total, including eight major bridges), the number of labourers involved (approximately two and a half million), the shortest time it took to complete the building, and the worst working environment. They had very little transportation facilities. No medical facility. Not only construction materials but even food was in short supply. Other than basic tools like hammers and spades there were no other tools to work with. They worked under the worst climatic conditions of the forest which was hot and humid. All these together make this railway work an extraordinary achievement."1

Post World War II

After the British captured Burma and Thailand on January 16, 1946, the British Army ordered the removal of a four kilometre railway line from Ni Thea to Sonkrai in Thailand using Japanese prisoners of war. Train links between Thailand and Burma were also cut off. This was done to protect Singapore from invasions. Thereafter the Burmese section of the railway was gradually cut short of operations and rendered unusable.

In October 1946, the Thai section of the railway was sold to the Thai government for 1,250,000 pounds. The amount was given as relief to the countries from which Japan took goods to build the railway. Following the death of the Minister of Transport of Thailand in a rail accident due to the collapse of a bridge near Konkoita on February 1, 1947, it was decided that it would be enough to operate the railway line till Nam Tok.

On June 24, 1949, the Thai Railway Department began repairing and restoring this railway line, which was completed on April 1, 1952. Even though the plan to restore and operate the Burmese section of the railway has been put forward several times, it has not been implemented. Burma region is mountainous. Since many new bridges and railway tunnels may be required, the plan was postponed. After the fall of Japan, efforts were made to repatriate prisoners and Asian labourers.

Labourers

Japanese Army

The Siam Death Railway was overseen by 12,000 Japanese soldiers. They include 800 Korean soldiers. They worked as railway engineers, supervisors and guards. Although the Japanese soldiers did not have a heavy workload, up to 1000 people died during the railway construction. Japanese soldiers were not only violent but also physically tortured the prisoners of war and other labourers. Labourers were continuously severely punished and humiliated.

Southeast Asian Labourers

The number of Southeast Asian labourers employed for this work was nearly 1,80,000. They were called rōmusha. Javanese, Malayan Tamils, Burmese, Chinese, Thais and other Southeast Asians were forced into labour by the Japanese army. Many died during its construction. Initially Burmese and Thais were employed in their respective countries, but the Thai workers escaped. The number of Burmese was not enough. The Burmese welcomed the Japanese invasion and also assisted Japan in the recruitment of labour.

The Japanese government who showed swiftness to build the railway bridge, advertised in the early 1943’s promising good wages and accommodation facilities to the labourers. When the people did not believe this, they were forcefully taken by the Japanese government to build the bridge. As stated by Neil MacPherson in his book Death Railway Movements, approximately 90,000 Burmese and 75,000 Malaysian Tamils were involved. According to several other documents, more than 100,000 Malay Tamils were brought under this project and more than 60,000 are said to have died.

British doctor and prisoner of war Robert Hardy wrote, "The situation in the riverside camps is dire. They were made to stay away from the Japanese and British camps. No toilets. British prisoners of war in the Kinsai-Yoke area had to bury an average of twenty coolies every day. They were all brought in with false promises from Malaya. They were told 'simple work, good pay, good housing’. Many had even brought their wives and children. On arrival they were confined in small tomb-like quarters. They were beaten and kicked by Korean and Japanese soldiers. They were unable to buy extra food, they did not even know what was going on, they lived there sick and scared. Yet they treated the sick British prisoners of war with conscience."

Prisoners of War

The first prisoners of war to go to Burma were 3,000 Australians who worked at the airport and in the interior before railway construction began. They were made to stay in the Changi camp. From there they were taken by train and boat to the Swarnapuri camp in Thailand and from there to various camps in Burma.

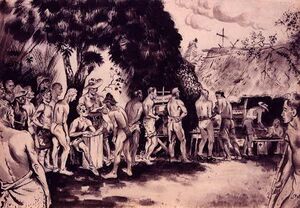

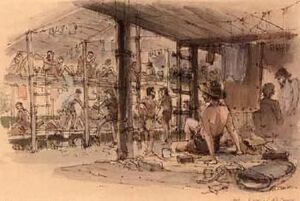

Subsequently, prisoners of war were brought in from Singapore and East Indies and established camps for a minimum of 1000 labourers at every 8-17 km of the route. The camps were built of thatched roofs and bamboo poles with the sides open. These camps were 50 metres in length. Platforms were raised from the ground on each side of a dirt floor. Each labourer was given a two-foot-wide space to sleep.

Even after the completion of the railway work, the prisoners of war were made to stay in the railway camps for another two years. A few of them were sent to Japan as manual labourers. Asian prisoners of war and Asian labourers were sent to the Kra Isthmus Railway project from Chumphon to Kra Buri in Indonesia, and to the Palembang Railway project from Pekanbaru to Muaro in Sumatra, Indonesia. Ten thousand prisoners of war were sent on ships to Japan. Many of them died due to bombing and disease.

After 1943, the situation of prisoners of war improved as the Allies began to raise their hands in World War II. After the bridge construction work, the remaining prisoners of war were sent to medical and rehabilitation centres. In the rehabilitation centres they built sheds of bamboo and palm fronds and performed music and drama to regain their motivation. Many people have recorded those days.

Brutality

Malaysian plantation workers, Indonesian workers were unaccustomed to the harsh conditions of the Burmese jungles. Malnutrition, physical abuse, malaria, cholera, dysentery and tropical ulcers were cited as common causes of death among construction workers. They were overburdened with work, but with very little food. They were kept in very poor condition.

The death toll in the construction of the Siam-Burma railway line varies from side to side. Of these, the Australian government’s statistics are most frequently cited by researchers. Accordingly, It is estimated that about 90,000 Asian workers and 16,000 prisoners of war died out of the 330,000 who worked on the construction. However, all parties agree that the death toll of Southeast Asian labourers was higher than that of military personnel. According to David Boggett, the death rate of Asian labourers was about half of the overall death rate. McPherson notes that the highest number of deaths were among Malayan Tamils and Javanese workers.

Medical Conditions

Different researches have shown that poor medical conditions in the camps were the primary cause of death. Japanese doctors and American and European doctors who were prisoners of war knew nothing about the diseases of the equatorial rainforest. Comparatively, the death rate in Dutch prisoners of war camps was relatively low. The reason was that they had immigrated to Burma a generation ago, many of them were born and raised there, and their doctors had knowledge of local diseases.

Medical services varied from camp to camp. There were three doctors in a camp with four hundred Dutch prisoners. No one died in their camp. Robert Charles recorded that when 190 American prisoners of war received medical treatment under Dr. Henry Hecking, only three died. But in another American camp of 450 people, a hundred died. Most of the camps in Malaysia and Java were without medical assistance.

According to statistics, prisoners of war had lost an additional 9 to 14 kg compared to the soldiers who served there. This is very dangerous and could cause loss of life.

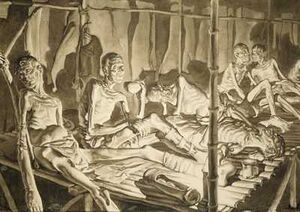

Records

Artists such as Jack Bridger Chalker, Philip Meninsky, John Mennie, Ashley George Old, and Ronald Searle, who had suffered in that terrible, dangerous environment, portrayed it as paintings. They had used human hair as brushes and plant juices and blood as paints. Their paintings on toilet paper have also been used as evidence in Japan's war crimes trial. Many of their paintings are housed in the Australian War Memorial, Victoria's State Library and the Imperial War Museum in London.

Railroad of Death, written by former prisoner of war John Coast in 1946, is considered an important direct document. He was the one who called this rail work the death railway. John Coast recorded the oppression and deaths of prisoners of war, life in those conditions and the condition of Burmese villages.

In his book Last Man Out, H. Robert Charles, a U.S. Marine Soldier and survivor of the USS Houston, recorded the experiences of Dr. Henri Hekking, a British prisoner.

Ernest Gordon, from Scotland, was a prisoner on the Siam Death Railway. His autobiography, 'Through the Valley of the Kwai’, was later made into a film in 2001, 'To End All Wars’.

But none of these records contain any significant depictions of South Asian labourers and Tamils perishing. One reason was that prisoners of war and labourers were segregated and kept separately. There is no formal documentation of mercenaries. Even memoirs were not made. Only after a long time did the Tamils start making memoirs. Half a century had passed by then and most of the mercenaries had passed away. The rest had very vague memories. Memoirs of British and Australian prisoners of war and other documents are also the historical evidence to record the destruction of the Tamils today.

Investigation of War Crimes

World countries including Singapore and Malaysia declared the construction of the Siam-Burma railway as a war crime. Japan was sued. At the end of World War II, 111 Japanese military officers were investigated for war crimes for behaving atrociously during railway construction. Out of which 32 people were sentenced to death. Lieutenant General Eiguma Ishida, one of the main commanders of the Burma-Siam railway construction, was convicted and sentenced to 10 years in prison after trial. His deputy officers Colonel Shigeo Nakamura, Colonel Tamie Ishii and Lieutenant Colonel Shoichi Yanagita were sentenced to death.

Hiroshi Abe, the first lieutenant to serve as Burma's chief superintendent of rail construction, was convicted and sentenced to death for the cholera outbreak in the camp at Sonkurai, which killed 600 of the 1,600 British soldiers. It was later commuted to life imprisonment. Major Sotomatsu Chida was sentenced to ten years in prison.

In general, these trials focused on the abuse of American and British prisoners of war. There was extensive evidence and documentation only for that. The deaths of Asian labourers were largely ignored. It did not come under the war crime category. No compensation was provided to the affected Southeast Asian labourers.

Notable Constructions

- Khwae Yai Bridge - Railway bridge over the River Kwai (322 metres)

- Wang Pho Viaduct – This is a wooden railway bridge (400m) that follows the cliff across the Kwai Noi River.

- Songkurai Bridge – A wooden bridge and railway (90 metres) over the Songkalia river.

Cemeteries

In 1946 the remains of those who had died in prisoners of war camps, the bodies of those who had been buried were recovered and transferred to the official war cemetery. There were several burial grounds along the 415 km long railway line. Those burial grounds were renovated into three permanent cemeteries and the bodies of prisoners of war were reburied. Among them, the bodies of 668 American soldiers were taken back to the United States. The Kanchanaburi War Cemetery, which is the primary Cemetery, is located in Kanchanaburi. There are 6,982 graves of British, Australian and Dutch prisoners of war. Of these, 6858 graves have been identified. 3,585 British prisoners, 1,896 Dutch prisoners and 1,362 Australian prisoners are buried here. 11 Indian soldiers who served in the British Army are also buried in the nearby Islamic cemetery.

There is another Cemetery, Chungkai War Cemetery, at Chung Kai near Kanchanaburi. It contains 1,693 war graves. They have been identified as 1373 British, 314 Dutch, 6 Indian Army.

There is a prisoner of war cemetery in Thanbyuzayat, Myanmar. All three cemeteries are maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Museums

Numerous memorials and museums have been set up for the people who died during this railway construction. The biggest museum among them is at Hellfire Pass, where many people lost their lives. There is a museum for Australian soldiers. Near Myanmar, there is a museum in the town of Thanbyuzayat. There are two more museums in Kanchanaburi, Thailand. Thailand-Burma Railway Centre opened a museum in January 2003 (JEATH War Museum). There is a commemorative notice on the kwai bridge. The train carriage that ran there is on display. There is also a memorial in England (National Memorial Arboretum ,England).

But there is no separate memorial or museum for the 60000 odd Tamil people who died on that railway. Neither their memories are properly compiled nor memoirs are collected.

Tamil Literary Records

News about the Tamils who passed away in the Siam Death Railway did not reach Tamil Nadu. Pa. Singaram, who was in Malaysia-Singapore during the war, did not record these atrocities in his novels Puyalile Oru Thoni and Kadulakku Appal, and recorded the history only from the side of the Japanese. M.S. Kalyanasundaram, who wrote the novel 'Iruvathu Varushangal’ with a war background, did not know about Siam Death Railway.

The Tamils who died in the Siam Death Railway were completely forgotten for a long time. It was in 1993 that the novel 'Siam Maranarayil’, written in Malaysia, introduced these atrocities to the Tamil literary scene. That too within the small circle of dedicated literary readers. But the novel fails to introduce Siam's Death Railway’s cruelty with actual intensity. So it did not receive enough attention. Not even a review was written for that novel.

News about the Siam Death Railway spread widely only after the introduction of the Internet after 2000. The news about it has still not reached the Tamil public yet. Not a single documentary has been made till 2022 in the Tamil Nadu Public Media. Until 2022, not a single document has been written after reviewing the place in the popular media. There is no record in Tamil cinema till 2022.

- Maravalli Kizhangu - S.A. Anbanandan - (Novelette - 1979)

- Siam Maranarail - R. Shanmugam - (Novel - 1993)

- Ninaivu Chinnam - R. Rengasamy - (Novel - 2005)

- Kaiyaru - Ko. Punniyavan - (Novel - 2021)

- Rail - Indrajit - (Novelette - 2021)

- Siam - Burma Marana Rail Padhai - C. Arun

Documentary

On behalf of the Nadodigal Creations, a documentary titled 'SIAM BURMA DEATH RAILWAY (Buried tears of Asian labourers)’ in English and 'SIAM-BURMA MARANARAIL PADHAI (Ezhudhapadadha Asia Tamilargalin Kanneer Kadhai)’ in Tamil has been made. (See Siam Death Railway Documentary)

Later Media Records

- 'The Bridge on the River Kwai' is a 1954 film directed by David Lean. It records about the British prisoners of war serving on the Siam Railway.

- The 2001 film 'End All Wars’ is based on the novel 'Through the Valley of the Kwai’ by Ernest Gordon.

- The Railway Man is a 2013 film directed by Jonathan Teplitzky. The background story of the film is Siam Death Railway.

References

- Siam Burma Marana Railpadhai - C. Arun (Research Book - 2008)

- Siam Marana Rail, Two Novels M. Navin

- Siam Marana Rail, Tamilargalin Varalaru

- Burma - Siam Marana Rail padhai: Kothu Kothaaga Irandha Tamilargal - Oru Ratha Sarithiram

- 106,000 Uyirgal (Out of which 60,000 Tamils) bali konda marana rail padhai ….!!!

- Siam Marana Rail Documentary - Jeyamohan.in

- Siam Marana Rail Documentary Preview

- Varalatrin Vandalin - Jeyamohan.in

- Siam Death Railway Photos Australian Archive

- https://mosaicscience.com/story/far-east-prisoners-of-war/

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120118163648/http://www.hellfirepass.com/historical_facts_hellfire_pass.html

- https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2016/07/09/stories-of-death-railway-heroes-to-be-kept-alive/

- https://kajomag.com/the-forgotten-malayan-labourers-of-burma-railway-during-wwii/

- https://web.archive.org/web/20160527140349/http://www.myonlinetour.com/thailand/TheBridgeOverTheRiverKwae/index.htm

- https://www.canveyisland.org/people-2/3-heroes/ashley_george_old-2/ashley_george_old

- https://www.pbs.org/wnet/secrets/the-bridges-of-the-thailand-burma-railway/178/

- Gamba, C. The National Union of Plantation workers

- Boggett, David. "Notes on the Thai-Burma Railway. Part II: Asian Romusha: The Silenced Voices of History" (PDF).

- https://www.singaporewarcrimestrials.com/case-summaries/detail/084

- https://www.generals.dk/general/Ishida/Eiguma/Japan.html

- Ishida Investigation News https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1254708

- https://www.theprisonerlist.com/the-film.html

- https://www.cofepow.org.uk/memories/taylor-frederick-noel

- The Death Railway A Dutch viewpoint

- Sears Eldredge (2014). The Thailand-Burma Railway: An Overview

- https://www.far-eastern-heroes.org.uk/harrys_war/html/thailand_to_burma_railway.htm

- https://www.uspowtbr.com/17g-hintok/

- Sikhs working on the Death Railway: Blood, toil, tears and sweat

Links

- https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/captiveaudiences/

- https://web.archive.org/web/20090704143550/http://dl.screenaustralia.gov.au/module/299/

- https://www.pows-of-japan.net/

- Kanchanaburi War Memorial

- Chungai War Memorial

Notable Books

- Beattie, Rod (2007). The Thai-Burma Railway. Thailand-Burma Railway Centre.

- Last Man Out: Surviving the Burma-Thailand Death Railway: A Memoir

- Blair, Clay, Jr.; Joan Blair (1979). Return from the River Kwa இணையநூலகம்

- Boulle, Pierre (1954). Bridge on the River Kwai. London: Secker & Warburg

- Blair, Clay, Jr.; Joan Blair (1979). Return from the River Kwai. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780671242787.

- Boulle, Pierre (1954). Bridge on the River Kwai. London: Secker & Warburg.

- Bradden, Russell (2001) [1951]. The Naked Island. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

- Bradley, James (1982). Towards The Setting Sun: An escape from the Thailand-Burma Railway, 1943. London and Chichester: Phillimore & Co. Ltd. ISBN 0-85033-467-5.

- Charles, H. Robert (2006). Last Man Out: Surviving the Burma-Thailand Death Railway: A Memoir. Minneapolis, MN: Zenith Press. ISBN 978-0760328200.

- Coast, John; Noszlopy, Laura; Nash, Justin (2014). Railroad of Death: The Original, Classic Account of the 'River Kwai' Railway. Newcastle: Myrmidon. ISBN 9781905802937.

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission (2000). The Burma-Siam Railway and its Cemeteries. England: Information sheet.

- Davies, Peter N. (1991). The Man Behind the Bridge: Colonel Toosey and the River Kwai. London: Athlone Press.

- Daws, Gavan (1994). Prisoners of the Japanese: POWs of World War II in the Pacific. New York: William Morrow & Co.

- Dunlop, E. E. (1986). The War Diaries of Weary Dunlop: Java and the Burma-Thailand Railway. Ringwood, Victoria, Aus: Penguin Books.

- Eldredge, Sears (2010). Captive Audiences/Captive Performers: Music and Theatre as Strategies for Survival on the Thailand-Burma Railway 1942–1945. Saint Paul, Minnesota, USA: Macalester College.

- Flanagan, Martin; Arch Flanagan (2005). The Line: A Man's Experience of the Burma Railway; A Son's Quest to Understand. Melbourne: One Day Hill. ISBN 9780975770818.

- Flanagan, Richard (2013). The Narrow Road to the Deep North. North Sydney, N.S.W.: Random House Australia. ISBN 9781741666700.

- Gordon, Ernest (1962). Through the Valley of the Kwai: From Death-Camp Despair to Spiritual Triumph. New York: Harper & Bros.

- Gordon, Ernest (2002). To End all Wars. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-711848-1.

- Hardie, Robert (1983). The Burma-Siam Railway: The Secret Diary of Dr. Robert Hardie, 1942–1945. London: Imperial War Museum.

- Harrison, Kenneth (1982). The Brave Japanese (Original title, The Road To Hiroshima, 1966). Guy Harrison. B003LSTW3O.

- Henderson, W. (1991). From China Burma India to the Kwai. Waco, Texas, USA: Texian Press.

- Hornfischer, James D. (2006). Ship of Ghosts. New York: Bantam. ISBN 978-0-553-38450-5.

- Kandler, Richard (2010). The Prisoner List: A true story of defeat, captivity and salvation in the Far East 1941–45. London: Marsworth Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9564881-0-7.

- Kinvig, Clifford (1992). River Kwai Railway: The Story of the Burma-Siam Railway. London: Brassey's. ISBN 0-08-037344-5.

- La Forte, Robert S. (1993). Building the Death Railway: The Ordeal of American POWs in Burma. Wilmington, Delaware, USA: SR Books.

- La Forte, Robert S.; et al., eds. (1994). With Only the Will to Live: Accounts of Americans in Japanese Prison Camps 1941–1945. Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources.

- Latimer, Jon (2004). Burma: The Forgotten War. London: John Murray.

- Lomax, Eric (1995). The Railway Man: A POW's Searing Account of War, Brutality and Forgiveness. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-03910-2.

- MacArthur, Brian (2005). Surviving the Sword: Prisoners of the Japanese in the Far East, 1942–1945. New York: Random House. ISBN 9781400064137.

- McLaggan, Douglas (1995). The Will to Survive, A Private's View as a POW. NSW, Australia: Kangaroo Press.

- Peek, Ian Denys (2003). One Fourteenth of an Elephant. Macmillan. ISBN 0-7329-1168-0.

- Rees, Laurence (2001). Horror in the East: Japan and the Atrocities of World War II. Boston: Da Capo Press.

- Reminick, Gerald (2002). Death's Railway: A Merchant Mariner on the River Kwai. Palo Alto, CA, USA: Glencannon Press.

- Reynolds, E. Bruce (2005). Thailand's Secret War: The Free Thai, OSS, and SOE During World War II. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Richards, Rowley; Marcia McEwan (1989). The Survival Factor. Sydney: Kangaroo Press. ISBN 0-86417-246-X.

- Rivett, Rohan D. (1946). Behind Bamboo. Sydney: Angus & Robertson (later Penguin, 1992). ISBN 0-14-014925-2.

- Searle, Ronald (1986). To the Kwai and Back: War Drawings. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press.

- Teel, Horace G. (1978). Our Days Were Years: History of the "Lost Battalion," 2nd Battalion, 36th Division. Quanah, TX, USA: Nortex Press.

- Thompson, Kyle (1994). A Thousand Cups of Rice: Surviving the Death Railway. Austin, TX, USA: Eakin Press.

- Urquhart, Alistair (2010). The Forgotten Highlander – My incredible story of survival during the war in the Far East. London, UK: Little, Brown. ISBN 9781408702116.

- Van der Molen, Evert (2012). Berichten van 612 aan het thuisfront – Zuidoost-Azië, 1940–1945 [Memoires of a Dutch POW who survived 15 camps on Java, in Thailand and in Japan] (in Dutch). Leiden, Netherlands: LUCAS. ISBN 978-90-819129-1-4.

- Velmans, Loet (2003). Long Way Back to the River Kwai: Memories of World War II. New York: Arcade Publishing.

- Waterford, Van (1994). Prisoners of the Japanese in World War II. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. Inc, Publishers.

- webster, Donovan (2003). The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theater in World War II. New York: Straus & Giroux.

- Wigmore, Lionel (1957). The Japanese Thrust – Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial.

✅Finalised Page